Lameness in the Horse

Equine

Every horse owner dreads the day they go out to ride or exercise their horse and notice that their equine athlete is lame. For a horse owner this can create a myriad of questions and concerns relating to what may have caused this lameness, how serious is the injury, what it is going to cost to fix my horse, etc, etc.

Calling your veterinarian and scheduling a lameness examine is the first step to fixing your lame horse. In the meantime your horse should be kept in a stall or small paddock until he or she can be examined by your veterinarian. You may administer Bute or Banamine while your horse is on stall rest, however your horse should not receive any Bute or Banamine at least 24 hours prior to the scheduled lameness exam. Bute or Banamine may mask the lameness and distort the lameness exam results.

Early diagnosis and appropriate (pin point) therapy is the best and quickest way to get your horse back to performing at a high level. An additional benefit to early diagnosis is the reduced amount of ongoing damage to the injured bone, joint, ligament or tendon. Pin point therapy involves treating a specific joint, ligament, tendon, etc that is causing the lameness rather than using a “shotgun” method of treating the entire horse with anti-inflammatories or supplements. Pin point therapy, which can only be initiated after appropriate diagnostics, will speed up the healing and decrease the risk of re-injury later. Frequently owners will opt for the “rest and time off” method of therapy, for their lame horse. In most cases this method will not resolve the lameness long term. It may fix the lameness for a short period but the underlying cause of lameness still has not been addressed.

One of the most useful lameness diagnostic tools available to veterinarians, a simple lameness exam. An important part of a thorough lameness examine includes a detailed history.

Some of the more common questions asked during the history include:

What supplements or medication the horse has received?

Any history of prior lameness or joint injections?

Last time the horse was shod or trimmed?

What is the horse used for?

How old is the horse?

How long has the horse currently been lame?

Did the lameness get better with rest?

Did the horse become lame while being ridden or while turned out?

During the lameness exam, your veterinarian is going to palpate for heat and/or swelling over your horse’s joints, ligaments and tendons. This heat and/or swelling can be a big clue to unravelling the lameness puzzle. The next step in the lameness exam is to watch the horse walk and trot on a flat, smooth, hard surface in a straight line and in a circle to the left and right. Depending on the type of lameness, your veterinarian may also ask you to ride the horse during the lameness exam. Your horse’s degree of lameness is graded on a 5 point scale that has been established by the American Association of Equine Practitioners. The following is an outline of the grading system according to this scale.

Lameness Scale

The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) developed a lameness scale to aid veterinarians and horse owners in communicating about cases and recordkeeping:

0: Lameness not perceptible under any circumstances.

1: Lameness is difficult to observe and is not consistently apparent, regardless of circumstances (e.g. under saddle, circling, inclines, hard surface, etc.).

2: Lameness is difficult to observe at a walk or when trotting in a straight line but consistently apparent under certain circumstances (e.g. weight-carrying, circling, inclines, hard surface, etc.).

3: Lameness is consistently observable at a trot under all circumstances.

4: Lameness is obvious at a walk.

5: Lameness produces minimal weight bearing in motion and/or at rest or a complete inability to move.

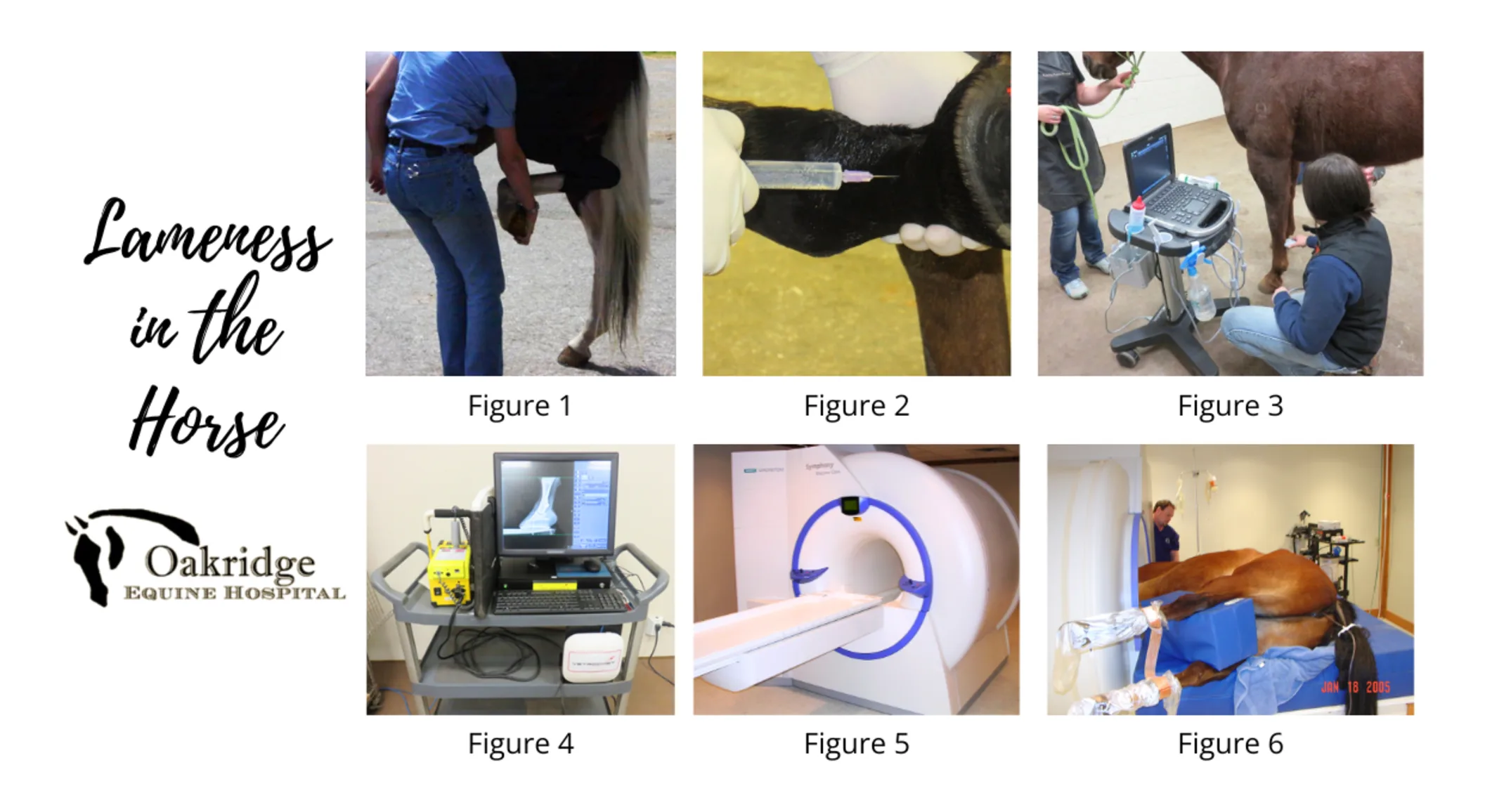

Once a baseline lameness is established, the next step will be to localize the cause of lameness by flexing joints (Figure 1), and performing nerve and/or joint blocks (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Picture of a horse having a hind limb flexion performed. This flexion is putting stress on the hocks and stifle. An increase in lameness following this flexion, could indicate a lameness originating from the hock or stifle.

Figure 2. Picture of a horse having a palmar digital nerve block performed. This block will numb the heels and the sole of the horse’s foot. If the lameness resolves with this block, that would be an indication that the source of lameness is in this region of the foot.

Local anesthetic can be injected into a joint or adjacent to a nerve, to numb a region of the horse’s leg. If the horse becomes sound after numbing a region of its leg, the source of lameness can be localized to that region of the leg. The next step is to perform an ultrasonographic (Figure 3 )and/or radiographic exam (Figure 4) on the region of the limb that is the source of lameness. Radiographs are better for imaging lesions or abnormalities in the bone, whereas ultrasonography is better suited for imaging lesions in the soft tissue.

Figure 3. Picture of an ultrasound exam being performed on a horse’s leg. This exam is being performed after the lameness was blocked out and radiographs were taken.

Figure 4. This is a picture of an x-ray machine used to take radiographs of horses.

In some instances, the cause of lameness cannot be identified with radiographs or ultrasonography. In these cases more advanced imaging may be needed such as MRI (Figure 5 and 6), nuclear scintigraphy and/or computed tomography. The down side to performing these advanced imaging techniques is their cost ($500-$2000) and the potential need for general anesthesia. The upside is the detailed images of the anatomical structures in your horse’s leg, which frequently result in accurate diagnosis for the cause of lameness.

Figure 5. Picture of the MRI located at Oakridge Equine Hospital. This MRIis used to perform MRI studies on horse’s lower limbs.

Figure 6. Picture of a horse under general anesthesia, while having an MRI performed on its front feet.

Occasionally a lameness exam is contraindicated because of a specific injury. For example, a lameness exam is contraindicated when a horse has a hairline fracture of the bone. Performing a lameness exam on a case with a hairline fracture could result in a complete fracture of the bone. If your veterinarian suspects a hairline bone fracture, which can be seen with a severe lameness (grade 4 or 5), your veterinarian may decide to take radiographs prior to performing any further test.

Successful lameness diagnosis takes a skilled veterinarian and an owner who can provide a detailed history. With today's advanced technologies, you have a better chance than ever of finding the problem and starting a treatment regimen that will bring your horse back to soundness.